GootLoader's "1,000-part ZIP" Trick: How Malformed Archives Crash Analysis Tools While Windows Still Opens the Payload

A new GootLoader 1,000-part ZIP archives delivery technique is a reminder that some of the most effective malware innovation is not in the payload itself, but in the packaging that prevents defenders from inspecting it.

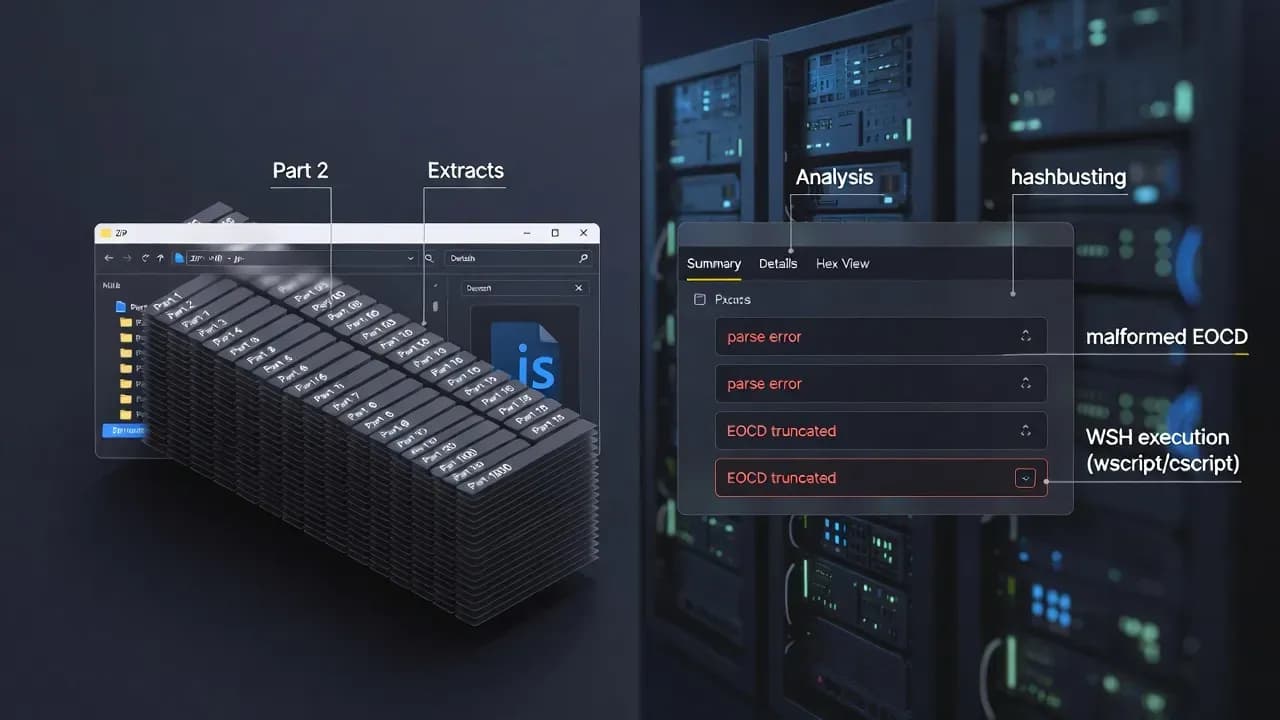

A new GootLoader 1,000-part ZIP archives delivery technique is a reminder that some of the most effective malware innovation is not in the payload itself, but in the packaging that prevents defenders from inspecting it. Instead of relying on a novel exploit, GootLoader operators are using deliberately malformed ZIP files assembled from hundreds of concatenated archives so that many security tools, sandboxes, and analyst workflows fail to unpack or even parse the content. The uncomfortable twist is that the method is "broken" in exactly the right way: Windows' built-in ZIP handling can still extract the malicious JavaScript (JScript), meaning victims can open it while many analysis pipelines crash, error out, or silently skip deeper inspection. This is not just a clever file-format hack. It is a practical anti-analysis strategy aimed at protecting the initial access stage that often precedes high-impact intrusions, including ransomware.

What happened: the technical breakdown of the concatenated ZIP delivery

At a high level, the new approach looks deceptively simple: a victim downloads a ZIP archive that contains a JScript payload, and the script launches via Windows Script Host. But under the hood, the ZIP is engineered as an adversarial object. Instead of a single valid archive structure, it is constructed by concatenating an unusually large number of ZIP archives back-to-back, typically in the range of several hundred and potentially reaching one thousand parts. This exploits how ZIP parsers commonly read from the end of the file to locate directory records. In practice, the archive "works" for Windows Explorer while failing for many third-party tools that incident responders and automated scanners depend on. The operator gets the best of both worlds: a user-friendly extraction path for the target and an unfriendly extraction path for defenders.

The technical choices are not random corruption. The malformed archive includes file-structure edge cases that trigger parsing failures, including a truncated End of Central Directory record and mismatched metadata between local headers and central directory entries. Randomized disk-number fields can also mislead tools into expecting a multi-disk archive sequence that does not exist. These are the kinds of details that do not matter to an end user clicking "Extract," but they matter to a sandbox that must reliably unpack and scan. The goal is straightforward: reduce the probability that the attachment is automatically detonated and classified before it reaches a human, and reduce the speed at which analysts can build robust signatures from a stable sample.

Why this matters operationally: breaking the defender toolchain, not just the file

Most organizations do not "analyze malware" as a single action. They operate a toolchain: email and web gateways detonate attachments, EDR sensors enrich events, sandboxes extract embedded objects, SIEM rules look for known artifact patterns, and responders use common unpacking tools to validate what a user downloaded. GootLoader's new ZIP design targets that entire pipeline. If the archive cannot be reliably opened by the tooling embedded in your security stack, your detection posture becomes dependent on second-order signals such as script execution, unusual child processes, and outbound network behavior. That is a weaker position because it pushes detection later in the kill chain, after the user has already opened the file and the script has already executed.

There is also a subtle "human operations" impact. When a ZIP fails to open in tools like 7-Zip or WinRAR, analysts often interpret it as a corrupt download rather than a deliberate evasion mechanism, especially if they are triaging at speed. In automation, failures may be treated as non-actionable ingestion errors or be excluded from deeper processing to keep pipelines stable. The adversary is effectively weaponizing reliability: they are not trying to hide the malware in perfect silence, they are trying to make the defender's systems unreliable when faced with this artifact. In security operations, unreliability is a real advantage for attackers, because reliability is what allows rapid scaling of detection, enrichment, and containment.

Threat actor incentives: initial access economics and why "delivery engineering" wins

GootLoader is commonly associated with initial access, not the final monetization event. In the modern cybercrime economy, initial access has value as a product. Operators that can consistently land a foothold inside enterprise Windows environments can monetize even if they do not run ransomware themselves. They can sell access, hand off sessions, or enable follow-on payload deployment. That business model rewards delivery engineering: it is more profitable to raise success rates and reduce early detection than to spend time building a bespoke payload that might still be caught at the distribution layer.

This also explains why file-format manipulation keeps evolving. Defenders have become better at blocking obvious macros, detecting simple script droppers, and flagging known loaders by hash. So the adversary shifts focus: make the same loader harder to inspect, harder to detonate, and harder to signature quickly. Expel's reporting describes this as "hashbusting" at scale: each download is generated uniquely, diminishing the value of static indicators. Mandiant's earlier research shows that GootLoader campaigns often start with a user searching for business-related documents and being lured to download a malicious archive from a compromised site. Combine those realities and you get a practical strategy: use search-driven distribution to reach the right users, then deliver a payload in a format that frustrates the very tools designed to classify it before execution.

How infection typically progresses after execution: scripts, persistence, and follow-on payloads

While the malformed ZIP is the headline, the post-execution workflow remains consistent with what makes GootLoader dangerous: it leverages Windows' own scripting and automation surfaces to bootstrap further stages. Once the extracted JScript is executed, it runs under Windows Script Host and can spawn PowerShell to continue the chain. Persistence mechanisms documented in recent reporting include using shortcut files in the Startup folder that re-trigger script execution on reboot, creating a repeatable foothold that survives a casual cleanup of the Downloads folder. This matters because it turns a user mistake into a stable access path, and it does so using artifact types that many environments still under-monitor.

From a threat hunting perspective, the more important point is that GootLoader is a loader. The loader's job is to pull down the next stage that aligns with the operator's current monetization plan. Mandiant's work details follow-on activity that can include additional payloads executed via PowerShell and stored in the registry, and it describes variants that reach out to multiple hard-coded URLs and send victim profiling information. You do not need every one of those behaviors to occur for the incident to be serious. If the ZIP and script execution succeeded, the environment should be treated as at risk for additional payload delivery. In practical response terms, the moment you see unexpected JScript execution from a web-downloaded archive, the "contain now, investigate in parallel" posture is justified.

How organizations can respond: containment priorities and a realistic IR workflow

If you suspect this GootLoader delivery method has reached your users, start with containment and triage that assumes the archive may be difficult to unpack in your usual tooling. Your first priority is not perfect static analysis of the ZIP. Your first priority is determining whether the JScript executed and whether it spawned follow-on processes. That means collecting endpoint telemetry for wscript.exe and cscript.exe executions, command lines, parent-child chains into PowerShell, and any persistence artifacts under user Startup locations. If you have centralized PowerShell logging, correlate script block events around the time of download and execution, and look for outbound connections that immediately follow script execution.

Containment should be pragmatic. Isolate affected endpoints quickly, because loader activity is time-sensitive and often hands off to other operators. Then inventory persistence: startup shortcuts, scheduled tasks, and suspicious script files placed in user-writable directories. If you run controlled folder access or application control, validate whether exceptions allowed script hosts to run untrusted content. For organizations with robust IR, the malformed ZIP can still be valuable: the very anomalies that break parsers can become a detection asset if you build file-format-aware rules. But do not let that become a bottleneck. You can block the execution path and disrupt the chain even if you do not immediately extract the script from the archive in a lab.

Prevention and detection strategies: hardening the weak points GootLoader relies on

Defenders should treat this as a forcing function to re-evaluate how their pipelines handle archive extraction failures. If your sandbox or gateway treats "could not unpack" as a benign error, you are providing attackers a reliable bypass lane. At minimum, extraction failures for web-downloaded archives should trigger escalation, secondary detonation paths, or quarantine. From a controls perspective, the highest-leverage mitigation is to reduce the blast radius of script execution. Many enterprises do not need Windows Script Host broadly enabled. If wscript.exe and cscript.exe are rarely required, restricting them through application control policies can sharply reduce the risk of this entire class of infections. If you must allow them, restrict their ability to execute downloaded content and monitor for suspicious execution from temporary or user-download directories.

Another practical mitigation is user experience engineering: change the default application for JScript files so that a double-click does not execute code. Making JScript open in a text editor by default converts "one click to execute" into "one click to view," which is a meaningful reduction in risk for a loader that depends on user execution. Finally, invest in behavior-based detection around the early chain: script host spawning PowerShell, unexpected persistence via startup artifacts, and rapid post-execution network beacons. GootLoader's delivery is trying to blind your static analysis. Your counter is to ensure that execution and post-execution telemetry remains visible, correlated, and actionable.

The GootLoader 1,000-part ZIP archives technique is effective because it targets a quiet assumption in modern defense: that we can reliably unpack, detonate, and classify what users download. When attackers make the archive itself hostile to analysis while keeping it compatible with the victim's default tooling, they shift the fight from static inspection to execution-time detection, where many environments are still uneven. The response is not to chase perfect file-format parsing everywhere, but to harden the execution surfaces GootLoader depends on, treat extraction failures as high-signal events, and correlate script-host behavior with persistence and network telemetry. Delivery tricks will keep evolving. If you can consistently stop script-based initial access from turning into durable footholds, you break the attacker's business model even when the ZIP looks "too broken to be dangerous."

Frequently Asked Questions

Not in the classic "inflate to consume disk" sense. The objective here is parser disruption and toolchain denial rather than storage exhaustion.

Different tools implement ZIP parsing differently, especially around edge cases and malformed fields. The attacker exploits those implementation differences.

Look for wscript.exe or cscript.exe running a .js or .jse file from user Downloads, Temp, or a newly created folder.

If your environment does not require Windows Script Host, restrict or block wscript.exe and cscript.exe.

Any organization where users routinely search for and download templates, agreements, and business documents is exposed.

Comments

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account to unlock exclusive member content, save your favorite articles, and join our community of IT professionals.

New here? Create a free account to get started.