LinkedIn Comment Reply Phishing: Fake "Policy Violation" Replies Abuse Trust, Notifications, and lnkd.in Links

Attackers are flooding LinkedIn posts with fake comment replies that mimic official policy violations, pushing victims to verify identity via lnkd.in links that hide phishing destinations.

Link length threshold that triggers LinkedIn automatic URL shortening

Common attack chain: restriction warning page, then credential harvesting

Opening: LinkedIn comment reply phishing exploits notification trust

A new LinkedIn phishing wave is exploiting something most security training barely covers: the credibility of public comment threads. Instead of sending obvious emails or DMs, attackers are flooding posts with fake "reply" comments that look like official LinkedIn enforcement messages, warning that an account is "temporarily restricted" and pushing victims to "verify" their identity through external links. Some of these links even use LinkedIn's own lnkd.in shortener, stripping away the most basic safety signal users rely on: being able to see where a link really goes before they click.

What is different this time: attackers are weaponizing the comment UI, not your inbox

Phishing on LinkedIn is not new, but the delivery channel is shifting in a way that is operationally important. A public comment is not just a message to one person. It is a visible, shareable object that can reach the poster, their audience, and anyone scrolling the thread. That changes the economics for attackers. One bot account can spray the same "enforcement" narrative across hundreds of posts in minutes, knowing that some percentage of targets will react emotionally, click fast, and self-compromise.

The trick is credibility by context. A "LinkedIn Security" style message posted under your own content feels more personal than a random email. It lands where you already expect feedback, replies, and platform notifications. It also benefits from social proof. If the comment has a logo, a company-style profile, and a confident tone, victims may treat it as a platform-level signal rather than a stranger's message.

This is why defenders should treat the campaign as a product-quality phishing tactic, not a crude scam. It is built to blend into everyday LinkedIn workflows, especially on mobile where UI constraints make verification harder.

The core lure: fake "policy violation" replies that create urgency and force action

The campaign commonly claims that the target has violated platform policies, engaged in non-compliant activity, or triggered "signs of unauthorized access." The message then escalates urgency: access is restricted, the account is limited, and the victim must click a link to restore normal status. In examples analyzed publicly, the language is designed to sound like a platform security control, not like a request from an individual.

This is classic social engineering with a professional-network twist:

Authority: the message poses as LinkedIn itself, often with official branding cues.

Urgency: account restriction is framed as immediate and consequential.

Action bias: a single button or link is presented as the only resolution path.

Fear of loss: creators and business users are primed to protect access, reputation, and reach.

If you manage a company page, recruit for a role, or rely on LinkedIn for sales pipeline, the emotional pressure is even higher. Attackers understand that. A compromised LinkedIn account is not only a personal loss. It can become an entry point into business conversations, supply chain trust, and relationship-based fraud.

Why lnkd.in makes this campaign harder to spot

A major reason this campaign is effective is that some links appear to be "LinkedIn links" because they are wrapped in lnkd.in. In normal usage, LinkedIn shortens long URLs in shared posts, and users see these shortened links as routine platform behavior. LinkedIn's help documentation explains that links longer than 26 characters may be automatically shortened after you click Post, specifically to make them easier to read.

Attackers are abusing that familiarity. When a suspicious destination is hidden behind lnkd.in, the visible domain becomes LinkedIn's, not the attacker's. On certain devices or UI views, the preview may not fully expose the final destination, and the user may click before they can evaluate the underlying URL.

This does not mean lnkd.in is unsafe by design. It means the shortener removes friction for legitimate sharing and removes friction for attackers at the same time. For defenders, the key lesson is simple: "looks like a LinkedIn link" is no longer a reliable trust signal.

A common attack chain: decoy restriction page, then credential harvesting

Public reporting on the campaign shows a two-step flow that is common in modern credential theft:

A first-stage page reinforces the narrative of restriction and urges identity verification.

A second-stage page performs the actual credential harvesting.

In observed examples, the initial page was hosted on a legitimate cloud hosting platform (for example, a Netlify subdomain), and the "Verify your identity" button forwarded victims to another phishing domain where credentials were collected.

This chaining serves multiple attacker goals:

Evasion: security scanners and casual users may stop at the first page, which looks like a warning portal rather than a login trap.

Flexibility: attackers can rotate the credential-harvesting endpoint without changing the public comment link everywhere.

Filtering: victims who continue to step two are more likely to comply with credential prompts.

Operationally, defenders should treat any "verify identity" demand that begins in comments as hostile by default. Legitimate platforms do not resolve account enforcement through public comment threads.

Fake company pages amplify trust and scale

Another notable element is the use of fake company pages that mimic LinkedIn branding and naming conventions. The objective is to look like an official platform entity, not a newly-created personal profile. Public reporting describes pages using LinkedIn's logo and name variations, and at least one such page was taken down during the response.

This matters because company pages inherit a different trust aura for many users. They look "organizational," and they align with how LinkedIn operates as a professional network. When that presentation is paired with urgent enforcement language, it creates a strong legitimacy illusion.

For LinkedIn users, the practical takeaway is that branding and page type are not identity proof. If the action requested is unusual, especially clicking external links from enforcement claims, you should default to verification through official, in-product pathways.

LinkedIn's position: policy violations are not communicated via public comments

LinkedIn has acknowledged awareness of the activity and stated that its teams are working to take action. Critically, a spokesperson emphasized a rule that users can turn into an immediate detection heuristic: LinkedIn does not communicate policy violations to members through public comments and users should report suspicious behavior.

That single statement is the campaign's Achilles heel. Attackers rely on victims believing the comment is an official enforcement message. If users internalize that LinkedIn does not enforce policy through comment threads, the scam's conversion rate collapses.

How to spot it quickly: practical checks that work on desktop and mobile

Most victims lose the moment they follow the attacker's flow. The goal is to break that flow early with low-friction checks:

Treat "account restricted" comments as hostile by default. A real platform enforcement action will appear in official notifications, email from an official domain, or account settings, not in a public comment.

Do not click the link to "verify" from the comment thread. Instead, open a new tab, navigate to LinkedIn directly, and check notifications and account settings there.

Long-press or hover to preview links where possible. If the UI allows it, inspect the destination and be suspicious of hosting platforms or unfamiliar domains.

Use a password manager as a tripwire. If autofill does not behave as expected on a "LinkedIn login," stop immediately.

If you already clicked, do not "test" credentials. Attackers often capture credentials on the first attempt and pivot to lock you out quickly.

The most reliable rule is behavioral: enforcement is resolved inside your account, not inside a comment.

What to do if you clicked or entered credentials: the containment playbook

If you interacted with the phishing flow, respond as if your account is already compromised. Speed matters because attackers often change recovery settings fast.

Reset your LinkedIn password immediately using a fresh session you initiated yourself (manual navigation, not the phishing path).

Review active sessions and sign out of sessions you do not recognize.

Check email address and phone number settings for unauthorized changes.

Enable MFA if you have not already, and prefer stronger methods where available.

Notify your organization if your LinkedIn account is connected to employer branding, recruiting workflows, or customer communications.

Warn your network if you suspect messages may have been sent from your account, since LinkedIn compromise is frequently used for follow-on fraud.

These steps align with general phishing-response guidance: pause, verify through official channels, report, and reset credentials immediately when exposure is suspected.

Closing

This campaign is effective because it attacks the interface, not the perimeter. By moving enforcement-themed lures into comment replies, scammers exploit notification habits, public trust, and the assumption that "platform-looking" messages are platform-owned. The abuse of lnkd.in adds another layer of credibility while removing visibility into the true destination. Defenders should update their mental model: phishing is not confined to email, and the safest verification path is always the one you initiate yourself inside the official product, not the one an attacker places inside a public thread.

Frequently Asked Questions

No. LinkedIn has stated that it does not communicate policy violations to members through public comments. Treat any comment claiming enforcement or restriction as suspicious and report it.

LinkedIn shortens long URLs in posts to make them easier to read, which normalizes the presence of shortened links. Attackers exploit that trust by hiding malicious destinations behind lnkd.in.

Beyond profile damage, attackers can impersonate you to scam your network, harvest leads, run recruitment fraud, or pivot into business relationships. Account takeover on LinkedIn is often monetized through trust, not through technical exploits.

Open LinkedIn directly in a new tab or the official app and check your notifications, security settings, and account access status there. Do not rely on comment-thread links to verify anything.

You are safer, but not necessarily "done." You may have revealed device and browser information and confirmed you are an active target. Monitor for follow-on messages and consider tightening your account security, including enabling MFA.

Related Incidents

View All High

HighMalicious Chrome Extension "MEXC API Automator" Steals MEXC API Keys and Silently Enables Withdrawals for Account Takeover

A malicious Chrome extension "MEXC API Automator" steals API keys during creation, silently enables withdrawal permissio...

High

HighBetterment Confirms Data Breach After Attackers Used Its Messaging Systems to Push a $10,000 "Triple Your Crypto" Scam

Betterment confirms a data breach after attackers leveraged its customer communications channel to distribute a high-pre...

High

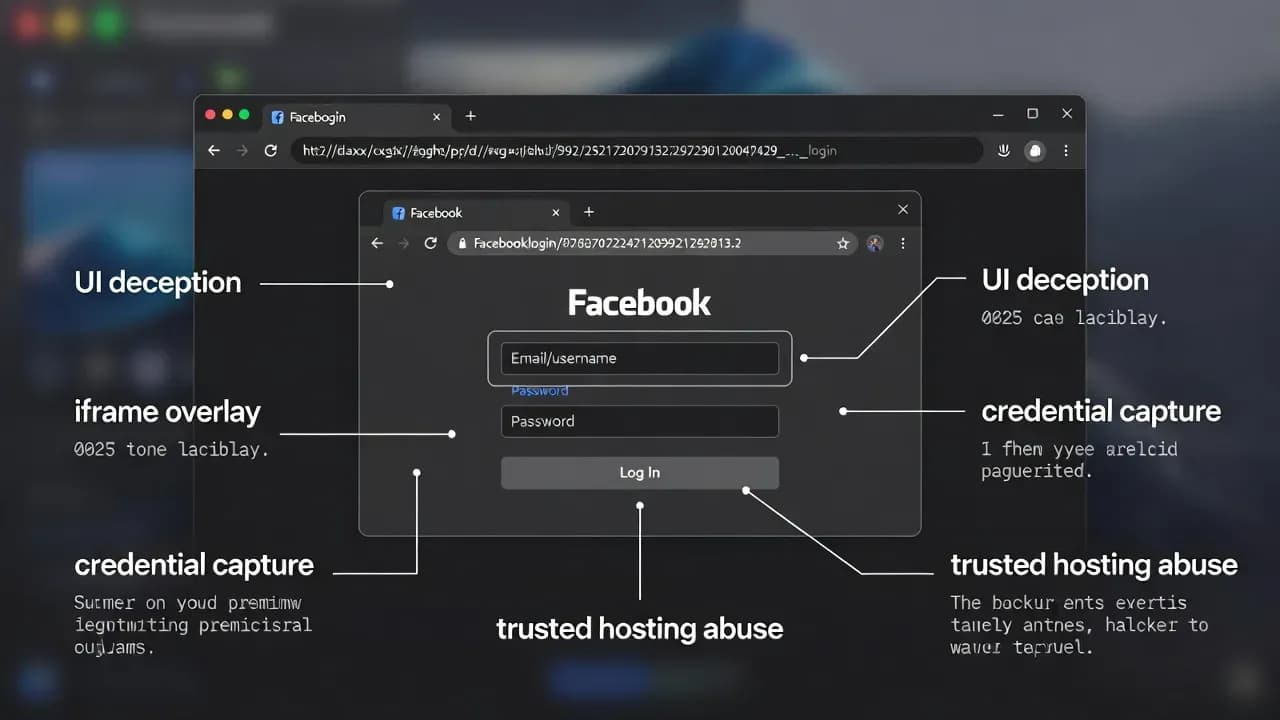

HighFacebook Credential Theft Surges With "Browser-in-Browser" Popups That Hide Phishing URLs in Plain Sight

Facebook credential theft is being amplified by Browser-in-Browser (BitB) phishing, which renders fake login popups with...

Comments

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account to unlock exclusive member content, save your favorite articles, and join our community of IT professionals.

New here? Create a free account to get started.