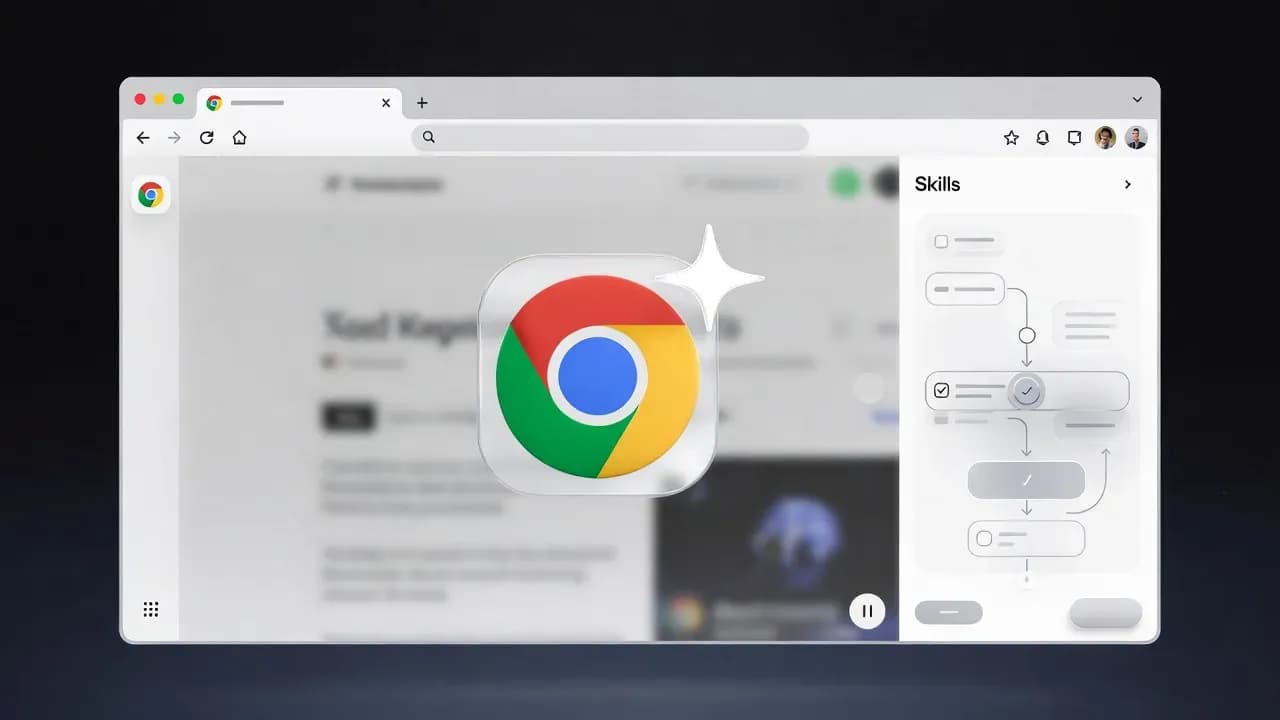

Google Chrome Tests Gemini-Powered "Skills" as the Browser Shifts Toward Agentic Automation

Google is testing a new "Skills" layer for Gemini in Chrome, including a chrome://skills page that suggests user-defined task automation. It is an early signal that the browser is evolving from a helper panel into an agent that can execute workflows, raising new questions about control, safety, and enterprise policy.

Google's browser is quietly approaching a turning point: Chrome is moving beyond AI that explains what you are looking at and toward AI that can do things for you. New testing around Gemini "Skills" in Chrome suggests an emerging layer where the assistant can be given named instructions to carry out specific tasks, not just answer questions in a sidebar. That is a meaningful shift because the browser remains the operating system for a huge share of modern work, from procurement and finance portals to HR systems and developer tooling. When automation arrives at that layer, it stops being a novelty feature and becomes a productivity and security story at the same time.

What makes this development especially notable is the direction of travel. Chrome's Gemini integration started as a contextual helper, something you opened when you needed a summary or a quick explanation. Skills implies a more durable concept: reusable behaviors, potentially tailored to the sites and workflows a user repeats every day. Even if the feature is early and hidden behind internal testing, the idea fits a broader pattern across the industry, where assistants are being redesigned into agents that can plan, act, and iterate, while the user stays in control.

How Chrome's Gemini foundation enables Skills

Chrome already has a foundation for context-aware assistance through Gemini, particularly in environments where the feature has been rolling out to eligible desktop users. In its current form, Gemini in Chrome behaves like a page-aware partner: it can look at the content you are reading, help unpack complicated passages, summarize long material, and reason across multiple tabs to compare options. That last capability is not trivial, because tab context turns the browser from a sequence of single pages into a working set, the same way a desktop user thinks about open documents. It also explains why Chrome is a natural home for "agentic" features, because the browser is where a user's intents and destinations are already visible.

Skills appears to be the next layer on top of that foundation, and the most concrete clue is the presence of a dedicated internal page, chrome://skills, that describes adding Skills with a name and instructions. The important detail is not the UI itself, but what it implies: a place where behaviors can be defined and managed, rather than a one-off prompt typed into a chat box. In parallel, the Chromium project has been evolving code paths that refer explicitly to a Skills feature, including work that introduces a feature flag to control when Skills is enabled. Feature flags are typical for capabilities that are being staged through development builds and experiments, which reinforces the idea that this is more than an idle string buried in a resource file.

From a product strategy perspective, Skills is also consistent with Google's public framing of where Gemini in Chrome is headed. Google has discussed "agentic" capabilities designed to handle tedious web tasks, such as booking appointments or ordering routine items, with user control to pause or stop actions. A Skills model fits neatly here: it is a way to give the agent boundaries and repeatable intent, and it provides a surface for users to understand what automation exists, how it behaves, and whether it should be trusted. The business value for Google is obvious: a browser that reduces friction becomes stickier, and an assistant that can execute workflows becomes harder to replace with a competitor's sidebar.

What Skills means for the browser market and web ecosystem

If Skills ships, it will accelerate a competitive dynamic already visible in browsers: the fight is no longer about who has the fastest renderer or the cleanest tab grouping, but about who owns the automation layer. Microsoft has been pushing Copilot deeper into Windows and its productivity stack, and other players are experimenting with agentic browsing experiences that blend search, summarization, and action. Chrome, with its distribution and default status across many environments, is uniquely positioned to normalize agentic browsing as a mainstream behavior. Once users expect their browser to complete tasks, not just display pages, the baseline for "modern browsing" shifts quickly.

This also changes how the web ecosystem thinks about automation. For years, browser automation lived in extensions, scripts, and testing frameworks, usually built by power users or teams with technical resources. An AI skills system potentially lowers that barrier dramatically, turning automation into something non-technical users can configure with natural language instructions. That is both exciting and destabilizing. It could unlock genuine productivity for individuals and small businesses, but it could also create new classes of failure, where an automation behaves incorrectly, acts on stale assumptions, or makes a judgment that the user would never have made.

Regulators and enterprise security teams will also pay attention because agentic browsing collapses several sensitive steps into a single interface. A browser that can summarize a page is mostly a content interpretation tool. A browser that can act is interacting with forms, accounts, transactions, and business processes. That raises questions about auditability, consent, and liability, especially in sectors where clicks can translate into financial commitments or data movement. Even without dramatic incidents, the mere presence of a skills system will pressure vendors to define clearer controls, and it will push organizations to decide whether browser-level agents should be enabled broadly, restricted to specific roles, or blocked entirely.

Why Skills is more like workflow automation than chatbots

The most interesting lens for Skills is not "Chrome gets smarter," but "Chrome becomes programmable for the average user." A named skill with instructions resembles a lightweight behavioral policy: when I am in this context, do this kind of work for me, using these rules. That is conceptually closer to workflow automation platforms than to chatbots, and it suggests Google is experimenting with a middle ground between free-form prompting and rigid scripting. If implemented well, it can provide the safety and predictability that raw prompts lack, while still being flexible enough to handle the messiness of real websites.

There is also a subtle but important difference between Skills and classic browser extensions. Extensions typically require installation, permissions, and updates, and they run as code. A Skills layer can be framed as user-defined intent, executed by the browser's own AI runtime, which may reduce the need for third-party code but increases the need for transparency. Users will reasonably ask what the skill can access, whether it can read across tabs, whether it can interact with logged-in sessions, and how it handles private content. For enterprise environments, this becomes a governance conversation: a skill might look like "just instructions," but the operational impact can resemble a macro that touches sensitive systems.

Finally, Skills hints at a future where the browser is no longer a passive container for web apps, but an active coordinator across them. Google has already positioned Gemini in Chrome as something that can work with the context of your open tabs and integrate with common Google services, which is a step toward cross-app orchestration without tab switching. Skills could become the user-facing mechanism that turns that orchestration into repeatable workflows, and it may also be the point where Google needs to define hard boundaries. Without guardrails, an agent that can act across tabs risks becoming a security and trust liability. With strong guardrails, it becomes a platform advantage.

What Skills means for users, developers, and enterprise IT

For individual users, the practical value of Skills will depend on whether it reliably reduces the chores of browsing rather than adding cognitive overhead. The best-case scenario is a set of small automations that feel obvious in retrospect, like extracting key details from a set of tabs, filling repetitive fields with confirmations, or turning scattered research into a structured summary without constant prompt rewriting. The risk is that an early implementation feels like another experimental surface that users must learn, which can limit adoption unless the system provides clear, trustworthy defaults.

For developers and web teams, Skills adds a new variable: how your site behaves under agentic interaction. If browsers begin acting on behalf of users, websites may need to consider how they present critical actions, how they confirm irreversible steps, and how they make state changes explicit. This is not about blocking automation, but about ensuring that legitimate user intent can be expressed safely, with clear checkpoints. It also reinforces the value of accessible, semantic UI, because agents that interpret pages will do better when the page is structured clearly.

For enterprises, the immediate implication is policy planning. Many organizations already treat AI assistants as controlled capabilities, with guidance around sensitive data and account actions. A skills-based agent inside the default browser will push that conversation into endpoint management, because it is not a separate tool employees opt into, it is potentially part of the browsing layer itself. IT teams should expect demand for clear controls, logging where appropriate, and predictable behavior across releases. Even if Google positions Skills as user-controlled and opt-in, enterprise buyers will want a consistent administrative story before they allow agentic automation near critical workflows.

The browser as the next AI deployment surface

Chrome's Gemini Skills testing is an early signal, but the direction is difficult to ignore: browsers are becoming action layers, not just viewing layers. A dedicated Skills surface suggests Google is working on a way to make agentic browsing more repeatable and more governable than free-form prompting, which is exactly what is needed if automation is going to become mainstream. The real test will be whether Google can combine capability with restraint, giving users and organizations confidence that automation remains controllable, explainable, and safe. If it gets that balance right, the browser may become the most important deployment surface for everyday AI agents in 2026.

Comments

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account to unlock exclusive member content, save your favorite articles, and join our community of IT professionals.

New here? Create a free account to get started.